By Johnny Hill

It is not by chance that Brady Corbet’s 215-minute American epic The Brutalist focuses intensely on the process of architecture – how the drawings and schematics evolve into something larger-than-life, something that dominates a landscape and something which may exist for centuries to come. Much like the process of erecting concrete slabs into walls and sky-high ceilings, filmmaking too exists within the realm of the auteur who must go through many hurdles to eventually create something, hopefully, grand. Whether the final creation of the monolith in The Brutalist or of Corbet and co-writer Mona Fastvold’s film itself is exactly what was imagined at the beginning of the projects, one thing remains certain – both the fictional László Tóth and Corbet himself have created something of ambition, something that once released into the world or integrated into the earth becomes a monument to the very act of human creation, irrespective of any political gain or interpretation.

Following thirty years in the life of Hungarian-Jewish architect László Tóth (Adrien Brody), The Brutalist is incredibly well-paced despite its length, with each scene never overstaying its welcome or being cut too short – leaving the film able to provide an epic of generational scale the likes of East of Eden without ever becoming uninteresting. Much like many of the Great American Novels, The Brutalist is doubly about the act of creation and the immigrant experience, with Tóth having escaped the Holocaust to live a new, unfamiliar life in America, where the promise of the American Dream allures artists as it does everyone. However, Corbet immediately recognises that by now, in the throes of late-stage capitalism, the audience will never ascribe to the hopeful optimism of the American Dream post-World War 2. Thus, the genius in The Brutalist’s opening scene is how it contrasts the hopeful immigrant against the disillusionment of capitalist ‘freedom’. As Tóth emerges from the dark bowels of a ship into the bursting, hopeful light of a new world, the camera presents a shaky image of the Statue of Liberty upside down and then sideways, indicating that, despite the hope present, this film will not indulge any naïve fantasies – something reflected in Daniel Blumberg’s excellent score of sweeping brass and minimal piano notes accompanied with the constant ticking of a clock.

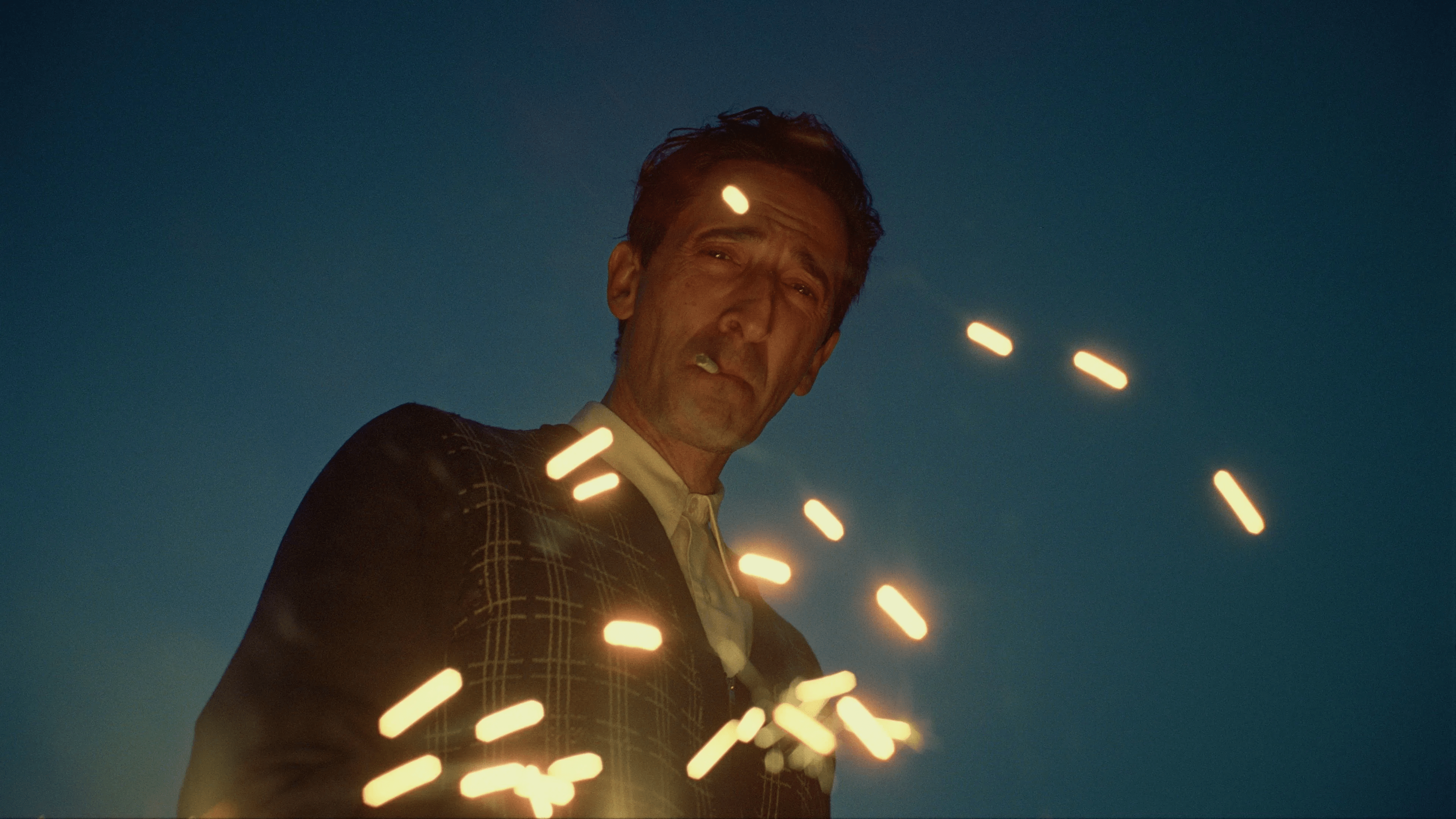

Instead, Adrien Brody plays Tóth how he does best – through high bursts of emotion and subtle melancholic scenes. Brody embodies the typical enigmatic artist who feels all emotions and translates them into his work. Alongside Felicity Jones’ desperate and aching performance as Erzébet Tóth, The Brutalist is a humanistic look into the life of those who live doubly out-of-place as aspiring artists and immigrants in a place that seems to regard them as cheap labour or as burdens on society. Whilst Brody and Jones’ accented but perfect English and lack of explication of their Hungarian backgrounds perhaps dulls the impact of showing the true immigrant experience of changing into drastically different worlds, The Brutalist still provides an analysis of the feeling of homelessness – and the channelling of this feeling into art or escapism.

Eventually, Tóth becomes involved with the wealthy American capitalist Harrison Lee Van Buren, brought to life by Guy Pearce’s welcoming and naïve acting that hides something sinister hidden beneath.. Through his cost-cuts and constant meddling, Corbet depicts how the American capitalist degrades the artist, the film slowly transforming into a darker picture of life as both an artist and immigrant. Whilst some of the dark choices in the second half of the film are certainly shocking, they also bluntly state the film’s central theses – fitting for the overall maximalist and in-your-face format of the film, including the seemingly out of place ending.

And maximalist the film certainty is. Lol Crawley’s gorgeous cinematography is regularly focused on those things larger than us – things accentuated by the excellent set design of Judy Becker. Frequently, the camera cranes upwards to look at towering buildings that rise into the sky, or at gigantic mountain ranges filled with marble, placing humans in perspective to gigantic structures that will likely last longer than those who created or harnessed them. Reflecting the recognition that these structures are essentially nothing more than their construction – as Tóth exclaims of his buildings in the film – there is also a joy of creation shown in the film’s cinematography. The exquisite framing of each shot where buildings and rooms unfold perfectly and lines match up symmetrically also speaks to the beauty of human feats of engineering – with one stand out scene leaving Tóth surrounded by his art, basking in the minimalist beauty of a simple chair in the middle of a library. Much like David Lynch’s Lost Highway, the camera also regularly takes the POV of a car speeding across the road – either behind another car or free, serving to remind the audience of the exhilaration of the artistic spark – a pure moment of flight across the countryside, free from the restraint of a typical viewpointe.

Whilst sometimes this maximalism suffers in the writing department – such as the overuse of news-radio exposition or somewhat forced emotional beats, these moments never last long enough to have an impact on the overall story of The Brutalist. Instead, they simply become swept up in the grand scale of the film, forming a part of the mythos rather than standing out from it.

Furthermore, Corbet’s choice to utilise the VistaVision format in filming also emulates some of the best American thrillers of Hitchcock, with Corbet’s use of this anachronistic format perhaps speaking to a metanarrative of artistic methods never fully fading into obscurity – much like the Brutalism movement – whilst also imbuing the film with the same feel of classic dramas.

While The Brutalist is certainly ambitious and blunt with the topics it seeks to tackle, perhaps a result of the young ambitiousness of a now 36-year-old Brady Corbet who, clearly inspired by academics such as Jean-Paul Sartre (just see The Childhood of a Leader), seeks to emulate the revolutionary spirit of freedom that existed in French philosophy post-May ’68, at no point does it devolve fully into pretension or over-the-top shock. Instead, The Brutalist seeks to stand as its own monument to art and humanity through its sheer ambitiousness. Much like how Tóth’s monument stands alone on a hill, representing achievement itself rather than just the jubilance, melancholy and obsession of its creator, Corbet’s The Brutalist stands as a testament to creative passion through its exhilarating grandeur. In 215 minutes, Corbet illustrates the wonders and terrors of creation, eventually announcing that the beauty of creation exists in the simple fact that something is created.

The Brutalist can be seen in cinemas now.