By Alexander Martin

It’s interesting, I think, that the posing of a question can often be infinitely more profound and thought-provoking than any answer could hope to be, and herein it is often apt for the question to remain solitary, the answers lingering around it with a kind of ethereal possibility. It is this purpose that enigma in film serves: to posit a question and withhold answers, to present a series of events with an apparent explanation that remains nonetheless elusive, to hide the truth from audiences – if any existed in the first place – and to let them seek it (or perhaps create it) for themselves.

This is not to suggest, however, that simply withholding information in a film is a hard and fast method of edification, not by any means. The craft of enigma is subtle and precarious: withhold too much, and the film is nonsensical; reveal more than is necessary, and the audience is left with answers that can ring dull and hollow.

The differences between the theatrical and director’s cuts of Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko demonstrate this fine line incredibly vividly. While it seems that in recent years it has become somewhat fashionable to criticise Kelly’s cult classic with a tinge of undeserved venom, its popularity would suggest that it is indeed worthy to be called a classic. Its status as such is, in part, a result of the questions it raises and never directly answers: are Donnie’s preternatural experiences real or a figment of his imagination (I’m aware that the ending indirectly answers this, but the question lingers nonetheless)? Why does this makeshift time loop exist in the first place? Why, in the end, do the characters appear to remember events that haven’t occurred (and never will)?

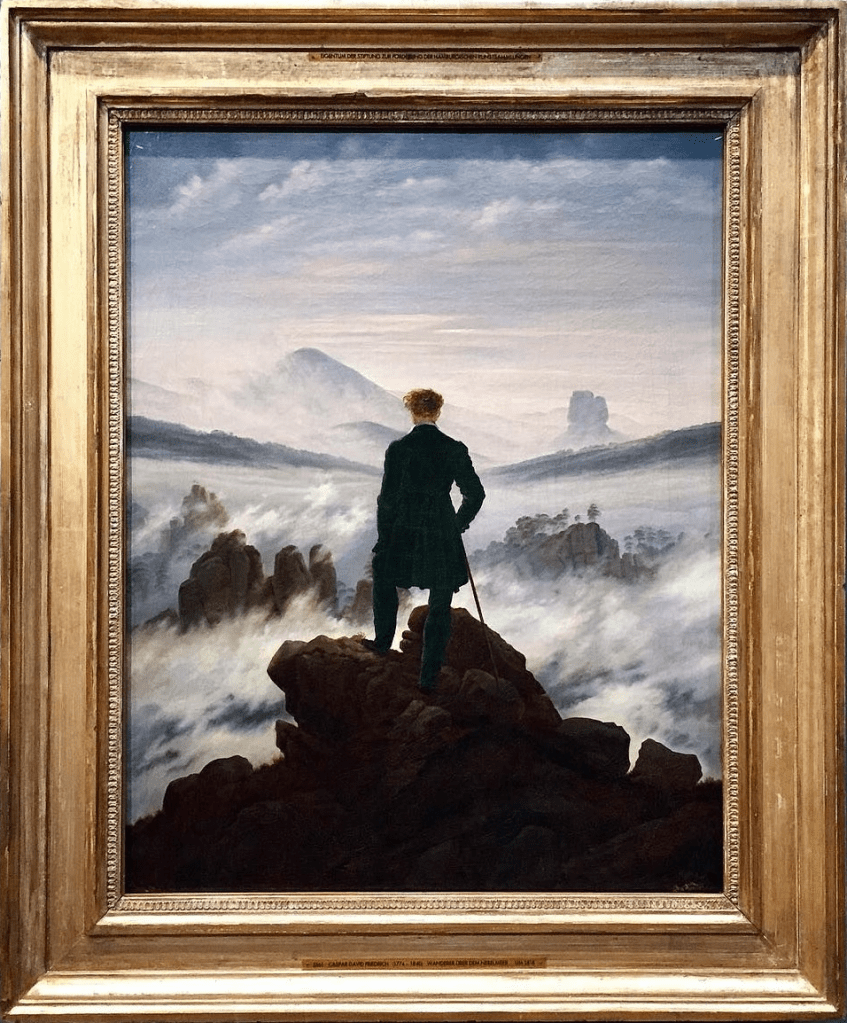

These uncertainties pervade one’s experience of the film and, in doing so, elevate it. It’s puzzling to me, then, that Kelly saw fit to remove this intrigue from the director’s cut, wherein excerpts of the film’s fictional book, The Philosophy of Time Travel, explain away the events as an unnecessarily complicated, jargon-riddled quandary of just that variety. Perhaps the level of certainty these excerpts provide satisfies some viewers with a comfortable, definitive answer to the film’s questions but, while definitive, the answer indeed rings dull and hollow to me. It’s akin to a fog obscuring what appears to be a masterpiece of a painting: though we can’t perceive it in its entirety, what we can see spurs contemplation as to what we cannot. We fill the blanks with our own interpretations, one no more or less concrete than the next, but each enhancing our experience. However, the fog soon clears, we see the piece in its entirety, and we realise that what we mistook for precise artistry is in fact clumsy happenstance, and with this knowing comes the empty feeling of disappointment.

I admit that I’ve seemingly bestowed Donnie Darko’s theatrical cut with the highest praise for its enigmatic method with hyperbolic phrases like ‘masterpiece’, but this is far from the truth. Undoubtedly, the film’s intrigue is enticing, but it’s nowhere near perfect given its penchant for obfuscating more than is necessary. I use it as an example simply because it’s an apt demonstration of the quality enigma can bestow upon a film, and how a slight alteration can besmirch it – the fine line.

One of the greatest uses of enigma in film can, in my opinion, be found in Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s 1997 film Cure. While perhaps the film is less inexplicable than, say, works by David Lynch such as Mulholland Drive or Lost Highway (which themselves make terrific use of enigma), it isn’t the pervasiveness of mystery that elevates this film, but the way in which it is crafted and used. In fact, I would go so far as to argue that the film isn’t inexplicable at all; it provides answers, but refrains from providing explanations (if such an assertion makes sense), and in doing so still manages to spur tantalising questions that are perhaps more compelling than if these answers had been omitted altogether.

Many of these regard the film’s antagonist, the apparently amnesiac psychology student Mamiya, who meanders around seemingly at random. His behaviour is reminiscent of that of a mischievous and malevolent deity; he appears seemingly out of nowhere, and extracts from people their innermost desires and compulsions. He has a name (and hence presumably relevant identification), he attended university (albeit sparsely), and his residence is filled with psychological research that provides some indication as to his behaviour. These serve as answers: he is ostensibly human, and his methods have been gleaned from years of research. Yet, despite this, questions linger: why does he feign memory loss? How does he choose his victims, if at all? Does he in fact possess what appears to be psychic powers? If not, how does he know so much about (some of) his victims? These lingering questions, too, are answered within the film, but the desire for finality is left unsatiated.

Cure’s enigma isn’t limited to Mamiya, but encompasses nearly every facet of the film: the protagonist, detective Takabe, the victims, the long-standing occult practices that underpin the film’s evil, and even the title itself. What is the cure? What is being cured? I have my own answers to these questions, and I won’t taint anyone’s viewing and interpretation of the film by sharing them. This is, in itself, evident of the value of enigma to a, and indeed this, film’s enjoyment; by sharing my own conclusions with people who haven’t watched it, ‘my’ answer may risk becoming ‘the’ answer as it moulds other potential interpretations and stifles the experience of the film and its enigmatic allure.

Enigma in film is diverse and extensive, and it’s impossible to fully dissect it through the discussion of two films. I can, however, draw several conclusions with some measure of certainty. The first is that it is indeed precarious, and involves a precise balance between what is shared with the audience and what is hidden. The second is that effective enigma in film is varied, and as such there exists no ‘rule’ to determine how much information should be revealed, and how much obscured to entice us. Furthermore – as already asserted – not every film can benefit from omission (indeed, many would regress in quality if it had been used). The effectiveness of enigma is entirely contextual, and in questioning which, if any, consistent rules exist regarding its use, one is ironically provided with few answers, and so instead must create their own.

Donnie Darko‘s theatrical cut can currently be watched on Stan in Australia, or rented through a variety of other services. Cure can currently be watched on YouTube here, or in higher quality by using ‘alternative’ distribution methods.